By: Richard W. Sharp

We set course for subjugation years ago. I should really say domestication. And it’s not because of the extension of government control, surveillance from microwaves, or the Statue of Liberty shooting out mind-control rays. The Man didn’t turn us into sheep; we’ve domesticated ourselves.

Structures of authority have a tendency to expand control, often overtly. There’s a cycle in which new governments are born in reaction to an existing authority burst forth with expanded freedoms, then slowly drift back toward authoritarianism through the restriction of those same freedoms in an attempt to protect the status of those in power (the American, French, Iranian, and Russian Revolutions, to cite only a few examples). A typical approach is to declare an emergency (real or invented) in response to some event and use prudence as cover for tightening of the noose (c.f. post-coup Turkey).

But the public often recognizes injustice in these attempts and resists; justifications put forth to explain actions such as Japanese internment during World War II have withered in the light of history.

A deeper threat to a free society, in which authority is based on the consent of the governed, is not overreach by the state, but our own, unconscious regulation of our thoughts and actions: self-censorship.

Ask not what the law can do to you, ask what you can do to preemptively apply the law to yourself.

Fear & goading: modes of self-censorship

To prove this, “let facts be submitted to a candid world.”

Self-censorship has different origins. It can be coerced, imposed by others through force or threats, or it may be arise on its own. Both modes are threats to free society. Both restrict the free exchange of ideas and both restrict the free exercise of one’s rights, although the second form is much harder to detect and overcome.

Self-censorship via coercion

Let’s start with an obvious form of censorship: pressure on the press. The press is often subjected to threats when they write write critically about powerful subjects, eliciting responses like:

- The crackdown on a free press in Turkey.

- The President’s least-favorite morning show.

Watched low rated @Morning_Joe for first time in long time. FAKE NEWS. He called me to stop a National Enquirer article. I said no! Bad show

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 30, 2017 - The regime warning the American People about their true enemy.

- Semi-serious joke threats (wink-wink, nudge-nudge) of violence towards the press.

#FraudNewsCNN #FNN pic.twitter.com/WYUnHjjUjg

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 2, 2017 - Literally body-slamming the press.

Self-censorship is well-established in these kinds of contexts. Reporters Without Borders publishes a press-freedom index ranking countries by the conditions faced by reporters in each (for the map and full report, click here ⇨  ). The freedom to decide what to publish and when may be be subject to official or semi-official censorship in the form of published or unwritten guidelines from the state, an independent press organization, or individual publication. Ultimately, however, the decision falls to the individual. What are the consequences of self-imposed censorship that shapes the choices made by individual publishers, editors, and reporters?

). The freedom to decide what to publish and when may be be subject to official or semi-official censorship in the form of published or unwritten guidelines from the state, an independent press organization, or individual publication. Ultimately, however, the decision falls to the individual. What are the consequences of self-imposed censorship that shapes the choices made by individual publishers, editors, and reporters?

The story of Blog del Narco is revealing.1 Blog del Narco became one of the most influential (and controversial) news outlets in Mexico by publishing uncensored descriptions, photographs, and videos of violence associated with the drug trade in Mexico. The argument was they best served the public, which suffers heavily from twin powers, government and “narcoterrorists,” by removing the media’s traditional editorial filters [Editor’s note: Don’t get any ideas, Rich]. In return for anonymity, BDN became a stage for independent reporting from both victims and perpetrators. The members of BDN thus became targets of real, not figurative, violence at the hands of anyone who held a grudge.

El Blog del Narco, 4 julio 2017.

One of the motivations behind creating BDN was that killings and other violence directed at reporters had led to a state of “‘autocensura,’ a term that reflects a situation that, while unlike direct, state-sponsored censorship is no less consequential in shaping and limiting coverage.”2 However, the anonymous and unfiltered approach taken by BDN (for its own reporters and its sources) did not solve the problem of self-censorship. BDN still faced the content-for-access trap. How did they justify writing in the name of the public, but simultaneously give known killers a stage on which to threaten rivals (unfiltered by the editor does not mean unfiltered by the source)? Leaving aside the ethics (for a minute) and focusing on the mechanics, this was the result of editorial decisions. What will be published or not, in whose name, and to whose benefit?

The fairly clear concept of coercive self-censorship (which sits comfortably in “I don’t like it, but I get it” territory) has drifted into the muddied waters of self-inflicted censorship. This is a messy business. The press is faced with a decision to publish certain content, not publish the content, to try to walk a line of alluding-to-but-not-overtly-publishing the content, or even to stop writing altogether. The freedom of the press to independently determine its course has been reduced not only by others, but by itself.

Self-inflicted doublethink

Overt coercion is one method for restricting people’s freedom of thought, and it is the more obvious situation. However, self-censorship can also be unconsciously applied. The slow shifting of norms from those that celebrate free expression to those that praise its circumscription is a slower process, but one that is usually more effective in the long run.

Consider the case of Reality Winner, who served in the Air Force before becoming an NSA contractor. She now stands accused of leaking a damaging report on Russian interference in the U.S. election to the press. We could discuss evolving norms in the U.S. around whistle-blowing, but the most startling statement on Winner doesn’t come from the pundits. It comes from Reality’s mother:

“I never thought this would be something she would do. She has expressed to me that she is not a fan of Trump – but she’s not someone who would go and riot or picket.”

It wasn’t always this way. We celebrate, today, this country’s founding: its open declaration of rebellion and not-particularly-peaceful-and-orderly acts of resistance. Its dedication to free expression, whether by religion, speech, press, assembly, or petition. The country was born by rioting and picketing in response to “a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.”

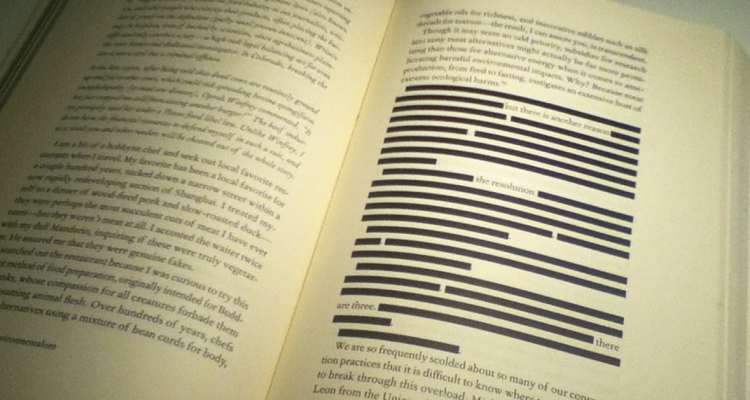

We celebrate this. Well, we celebrate the mythical canon, but contemporary protests are generally not analyzed in the same context of legitimate protest (unless the protesters are white and middle-class. Black Lives Matter need not apply.) It is the expression of modern doublethink. Self-censorship is a method for rationalizing the conflict between support for the manifestation of an ideal for the ideal itself.3

OK, let’s step down from the soapbox for a minute and look for some other examples of self-censorship that have arisen from a change over time in what we consider normal to the advantage of centralized power. Here a local example that startled me recently. Seattle’s light-rail system has fare enforcement officers. Riders are on their honor to purchase tickets, but may face random checks when they are on the train. The officers board the train as teams at both ends of the car at once, to cut off escape, and announce their presence. They wear uniforms, protective vests, and while they typically issue a warning, they do demand your ID and may ticket you. They do face uncooperative and dangerous individuals. What’s the big deal? Why did this make me question my own censura? Because I had to go through this experience for a number of years before ever wondering what happened to conductors, the civil authority that used to (and in places still does) carry out this task.

Just your friendly neighborhood watch. Image credit: MCDOT

When had a civil task become a police action? Why hadn’t I noticed? Here was an example self-censorship in myself: I had been blind to the the fact that I had surrendered a piece of my autonomy in public to policing (i.e., making a moral decision to buy a ticket instead of a legal one). Self-censorship through acquiescence.

A similar example is the presence of police officers in schools. It is an increasingly popular practice that originated in a desire to make schools safer for children. However, an unintended side-effect is that children are arrested instead of sent to the principle for unruly behavior. Yes, there will be cases when children behave criminally and arrest is required, however, viewing a police officer as a school resource invites authority to view children’s behavior as criminal rather than adolescent.

It can be hard to pin down when these shifts in norms occurred, but one source we can track is the emergence of language in print associated with the shift. The phrase “illegal immigrant” provides a clear example. From a historical viewpoint, it’s surprising to see a the term applied to what we’re taught in our public schools is a “nation of immigrants.” In this case, we can put some pretty firm dates on the rise of the term.

Frequency of the phrase “illegal immigrant” and derivatives over time (Google Ngram Viewer).

The term rises to prominence under the Clinton administration, a period of expanding criminalization and broadening of the definition of “moral turpitude” in legislation.4 Who gives it a second thought now when somebody uses the adjective, illegal as a noun? Who gives it a second thought when the term is applied to a child who was brought into the country without authorization? Who gives it a second thought when applied to a child born in this country, and therefore a citizen, to a parent without authorization? Who gives it a second thought when this term is applied to a human being? By failing to give it thought, I am self-censoring.

“But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.”5

Conclusions

Much has been made of Trump as a harbinger of totalitarianism, but he is more symptom than disease. We still elect our leaders in free and fair(ish) elections. If leaders come to power who would weaken our freedomes, it is a choice we made for ourselves. Self-censorship is one factor that can lead to this, but the process does not play out overnight.

Self-censorship in American political thought is even more surprising because the American tradition calls out against the surrender of freedom.6 On the other hand, perhaps this makes it inevitable. When we reflect on ourselves as protagonists, what examples do we choose to follow? Often we cast ourselves in the role of the freedom fighter from our own Revolutionary history, literature such as Orwell’s 1984, or films like 2005’s V for Vendetta. Censorship, however applied, is bad.

Self-censorship provides a way to cope with the conflicts that arise when we hold our ideals up to practice. We readily appeal to “all men are created equal” and The Greatest Generation, but neglect the history of race in America from 3/5ths to the present day, Japanese internment, and other injustices. It is tempting, but comes at a cost. It is the surrender of freedom for comfort.

Appealing to our ideals is not the problem, they represent some of the best ideas and intentions from our past. The danger lies in accepting them without question. As Edward R. Murrow put it, confusing “dissent with disloyalty,” especially when this leads to the choice to stifle dissent within ourselves. I wish I had come across Murrow’s March 9, 1954 broadcast in response to McCarthy earlier on in the writing of this piece since he has a gift for clarity and brevity that I lack. I leave the last words to him.

We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep in our history and our doctrine, and remember that we are not descended from fearful men — not from men who feared to write, to speak, to associate and to defend causes that were, for the moment, unpopular.

…

The actions of the junior Senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay amongst our allies abroad, and given considerable comfort to our enemies. And whose fault is that? Not really his. He didn’t create this situation of fear; he merely exploited it — and rather successfully. Cassius was right. “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.”

Edward R. Murrow, 1954

Notes:

1 The term self-censorship in this article is derived from the use of autocensura in Eiss’s paper. This author is indebted to the other work for the detailed analysis and focus on individuals’ decisions.

Paul Eiss, “Front Lines and Back Channels: The Fractal Publics of El Blog del Narco,” in Paul Gillingham, Michael Lettieri, and Benjamin Smith eds., Journalism, Satire and Censorship in Mexico, 1910-2014 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, forthcoming).^

2 Ibid. ^

3 Espoused vs. written or practiced – the ideal of all men created equal in the face of the written law of 3/5ths and denial of the vote to women, etc. ^

4 Thanks to Valery Hunt for an enlightening discussion related to the expansion of “moral turpitude”. ^

5 George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (London: Harvill Secker, 1949). But you knew that already.^

6 Very clearly, and with much Bold And Capitalized Print in an email I received from the Second Amendment Foundation this morning: “They May Try… But They’ll Never Take Our Freedom!” ^

No Comments on "Autocorrect rules us all: Real-life self-censorship"