By: Richard W. Sharp

Another season of head-pounding professional football draws to a close and the nation’s annual pageant approaches. It’s time to reflect and take account of what we’ve learned about concussions and CTE this year.

The main lesson isn’t very surprising: to date, the only widely reported successful approaches for reducing concussions are policies that reduce contact, primarily in practice. However, a major review of the current scientific consensus is underway, and we eagerly await the imminent summary statement from the 5th International Consensus Conference on Concussion in Sport.

Despite our incomplete understanding of CTE, the message has been sinking in. We saw several players walk away from the game at the beginning of the season, including top-tier athletes in their prime. Participation at the youth level has slumped over the past six seasons. Awareness of the issue is so widespread that Hollywood gave the issue the full Erin Brokovich treatment in 2015’s Concussion, a courageous take considering that the target is a popular corporate behemoth with tens of billions of dollars at stake and an image to protect.

But football has a special allure. It survived a similar crisis in the past, and has grown into a system capable of bending other institutions according to its whims. The picture painted in our first piece of a simple parenting choice is only a part of the story, and there are significant reason why playing the game, while clearly real and significant risk, is an understandable choice; one that I might make too if I walked in another’s shoes.

If you want to reduce concussions, then reduce contact

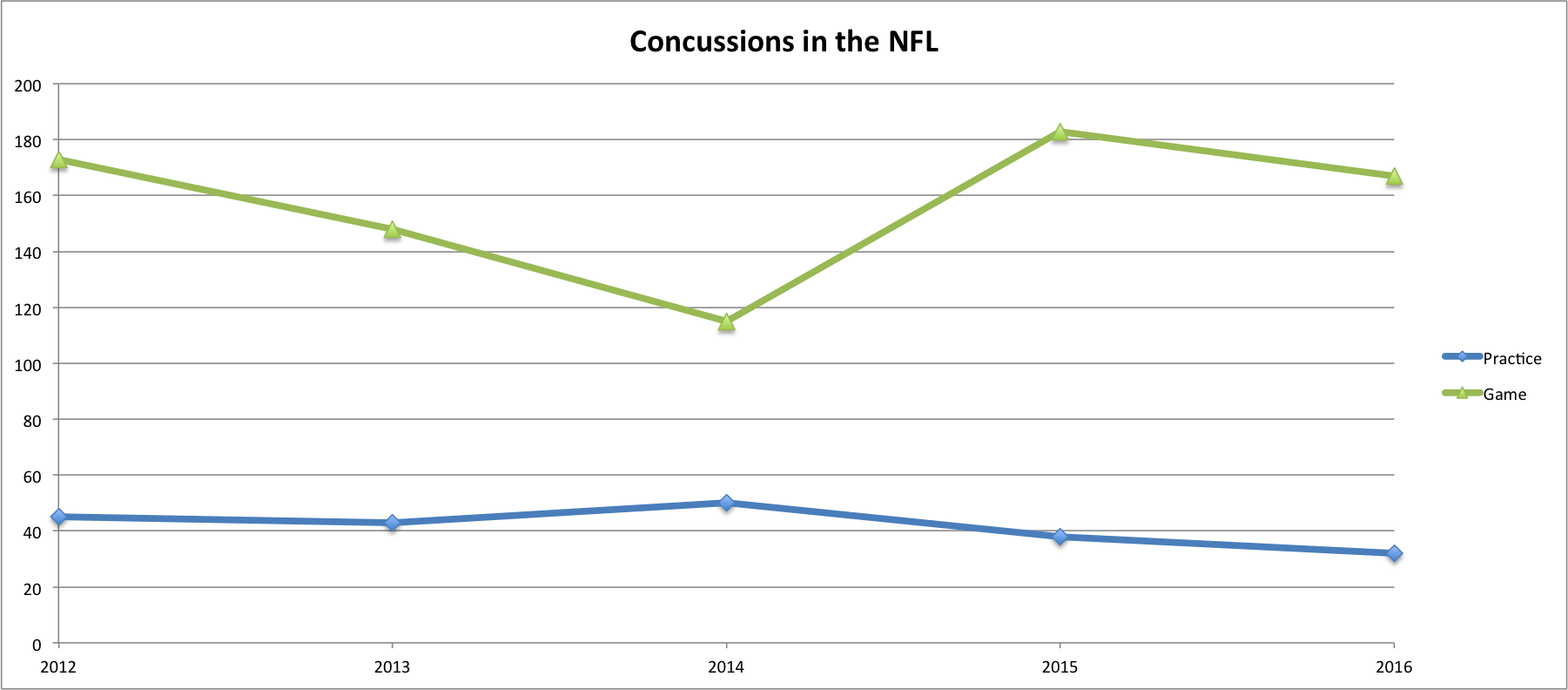

In response the the concussion crisis, the NFL and youth leagues have responded by reducing the amount of contact allowed in practice. This came to the NFL in 2012 via the 2011 collective bargaining agreement, and in rules changes in Pop Warner Football also instituted in 2012. The NFL has released injury statistics in the subsequent seasons, including concussion numbers. The number of concussions during practice has slightly decreased in that time and there have been no change to in-game numbers. Although the league and journalists are eager to explain why the numbers change each year, for example the 2015 headlines declaring a 25% drop, the numbers themselves don’t paint a conclusive picture.1, 2 What’s missing is where the numbers were before the new CBA. In fact, it would actually be expected and good to see the injury numbers go up, not because the game actually became more dangerous, but due to higher reporting standards and intensified monitoring to detect concussions.3

To get a handle on what a significant drop in the number of concussions would look like, let’s try a simple model. Suppose we think of concussions the way we think of coin flips: in any game, or any individual play could result in a concussion, or not. There were about 32,734 plays in the regular season, and 157 concussions, on average, over the past five years. Let’s assume that there has not been any significant change in the concussion rate in that time, then, we would expect between, roughly, 130 and 180 concussions in any given year (at a 95% confidence level). This is right in line with what we’ve observed. The picture doesn’t change much if you use the number of games instead of the number of individual plays in the model. The interval tightens to between 140 and 170, which is still in line with what we’re seeing. This isn’t proof that nothing has improved, but it is a statement that it’s hard to tell the difference between what we’re seeing and what we’d expect to see by chance alone: it walks like a duck.

However, there are some solid numbers at the youth level. A 2015 study of injury rate in youth football found that in Pop Warner the incidence of concussions in practice was significantly lower than the rates in other leagues. There was no similar reduction in games in which contact cannot be meaningfully reduced without rule changes that would significantly alter the game. This reduction comes down to something pretty basic: Pop Warner reduced the kind of contact allowed in practice, and sharply reduced the amount of time allowed for contact in training.

A second study from Virginia Tech identified particular drills that are especially dangerous. The numbers show that eliminating these specific drills from practice reduced the risk of head injuries. Again, while some combination of rules changes and technological advances may improve player safety in the future, the only currently proven method for reducing head injuries has been to reduce contact.

The altar of technology

Faced with the prospect of dark Sundays we have turned to our faith in technology, our collective and unwavering belief that we can science our way out of this. Certainly science can solve this; certainly all that is required is the will and and an outlay of capital (ok, maybe a lot of capital). There must be some amount of money that can be spent to make this simple and inconvenient hypothesis that head trauma causes brain damage go away.

The NFL thinks that number is at least $100 million, and announced a major investment in concussion R&D this year. $60 million is earmarked for technology like better helmets and the remainder to better understanding the long-term effects of head trauma. Nevertheless, technology does have a role to play in this debate, and there have many attempts to make the game safer through such means.

Helmets are big business

Most of the attention is directed at improving helmet technology, as most of today’s helmets are not radically different than the ones used in the 1970s. They consist of a hard outer shell filled with some material to cushion the impact. The NFL has partnered with the Army to use helmet-based sensors to help detect and diagnose brain injuries. Helmet manufacturers have introduced new features to further reduce energy transfer to a player’s head, such as a closer fit and deformable outer components. These have led to improvements, and earned “highest” ratings from safety rating agencies.4

However, all helmets still carry a nagging all-caps disclaimer: “WARNING: NO HELMET CAN PREVENT SERIOUS HEAD OR NECK INJURIES A PLAYER MIGHT RECEIVE WHILE PARTICIPATING IN FOOTBALL.“

Reduced risk also comes at a price, often about $400.

What do you call a tackling dummy with AI?

My personal favorite tech-based response to concussions is: call in the robots! When money really is no object, because, after all, this is football, why not remove one of the humans from a tackling drill and replace him with a robot? Actually, the approach is really sound and deserves to be emulated by those who can afford it. This will, as we have seen, reduce the number of TBIs suffered by a team as a whole because at least one lucky kid doesn’t get hit in the head.

Taking it on the chin, for science!

Better sensors for better understanding of impacts

One very interesting piece of research has been the introduction of impact sensors in the mouthpiece instead of the helmet (caveat: the study does not yet appear to be peer reviewed). While the helmet can be jostled around the head, the theory here is that the mouthpiece is in rock solid step with the rest of your skull during a violent impact. The impact data gleaned from these sensors has been fed into a model that simulates the elastic deformation of the brain during an impact. One of the critical findings is that some of the most intense deformation occurs deep inside the brain, and not just on the surface. This suggests that the popular conception of a nut rattling around in a shell isn’t complete, instead, your brain is more jello-ish.

This is your brain on elastic deformation.

The concussion crisis: we’ve been here before

Football faced a similar crisis a century ago. In the early 1900s, players were being killed at an alarming rate, leading the Chicago Tribune to label the 1905 season a “death harvest”. Teddy Roosevelt summoned the heads of major colleges to the White House to hammer out an agreement to reduce the most dangerous aspects of the game. 1906 saw major changes such as the introduction of the forward pass and neutral zone (though it was still some time before helmets came along). By opening up the field of play, the no-holds-barred piles of the good-old-old-days were swept away. Still, some did not feel this went far enough and banned the sport altogether (including the Trib’s hometown team, Northwestern).

This time around, public outcry has taken a different form, but it has been heard nonetheless. There has been a steep decline in participation at the youth level, from 3 million in 2010 to 2.2 million in 2015. Even worse (if you’re a billionaire with a football franchise), TV ratings, the NFL’s biggest bargaining chip, have taken a dive this year.5

The response so far seems to be the same in this century as it was in the last: reduce risk through rules changes or risk being shut down by law or obsolescence. USA Football, the governing body for youth football, has just announced its intent to make major changes to the game for by children by introducing a new format called “modified tackle.” Fewer players are set on a smaller field, kickoffs and punts are eliminated, and the approach is meant to generally reduce the severity of contact.6

The NFL has also introduced its own safety related rules changes in recent years, but compared to the situation in 1905, there are two new twists: money and technology. Money has worked its corrupting influence on the game for decades now, creating an interlocking system of dependents (broadcasters, educators, scientists, and government) willing to pervert their principles. Technology holds the allure of the quick fix: isn’t there some helmet design that can save us from Newton’s second law?

Choice, in the context of the system

So here we are, at the outset of 2017 faced with an untenable situation that we can’t quit. Despite evidence that links play to CTE and a failure to make any meaningful progress in safety other than to remove the contact, the core aspect of the game, we, the public, can’t stop watching. It doesn’t help that the league keeps promoting the idea of a scientific solution, and the military-industrial-complex-like arrangement that exists between the NFL, broadcasters, educators, scientists, and government bodies continues to promote America’s most popular sport. The existence of this last makes a parent’s or a player’s decision much more difficult when it comes to football than for most other sports because it, along with football culture, sets the context in which the choice is made.

Institutional participants in the football ecosystem cannot seem to live up to their principles. At the top, the league itself puts out statements claiming that “Player safety is the top priority for the NFL,” but nevertheless has been guilty of suppressing safety information if it threatens the bottom line. Broadcasters have yielded editorial independence for a piece of the pie. The semi-official party mouthpiece of the NFL, ESPN, has a record of rosy headlines (those TV numbers aren’t down for the year, they’re “up since the election!”) and cancelled productions at the request of their “partner”. Educators, primarily those running minor league football franchises under the auspices of the NCAA, have been willing to pay football coaches more than any other state employee and place player eligibility above player education. Scientists, “independent studies” have shown, don’t guard their independence as jealously as the public deserves, and government at all levels, from the NFL’s anti-trust exemption to the payment of stadium ransoms, bends over backwards to redistribute wealth to the 1% rather than stand for the public good.

Real good also comes from sport, and a player or parent will also consider this. In addition to providing a general opportunity to learn inherent virtue of teamwork, it is important to understand the benefits football can provide low-income students from “dropout-prevention,” to a path to higher education, and for a lucky few, the significant financial and social rewards bestowed on top-tier players.

It is important to remember that the choice occurs in real-world communities and not a laboratory. In some communities, the strength of support is near-universal and to not play may invite censure. The Michael Irvin put it well: “When we start talking about ‘Will parents stop letting their kids play?,’ well, some parents will have that opportunity. But many will not. They will say, ‘Son, this is your best chance.’”

1 When the numbers went up in 2015 it was because “Clearly… we’ve lowered the threshold for diagnosing concussion” and therefore more are being reported. When the numbers came back down in 2016 Jeff Miller, NFL senior VP of health and safety was pleased that “players are changing the way they’re tackling.”^

2 Top line numbers like this, declaring a large percentage gain in something good or drop in something bad are a favorite editorial trick (of which scientists are just as guilty as journalists). It sounds big and obscures the scale of the effect: what is big anyway in the particular context? Where are the error bars?^

3 The doctors are perplexed. “Why would ‘the numbers keep going down,’ asked Matthew Matava, the St. Louis Rams’ team doctor … ‘Because you’d think, with more vigilance, you’d see more of any sort of condition,'” a sentiment also echoed by William B. Barr, the director of the neuropsychology division at the N.Y.U. School of Medicine, who has worked with the Jets.^

4 An excellent example of highest != high.^

5 On the upside, this has spawned a cottage industry to explain why.^

6 Any rules changes tend to result in a backlash by the purists, even though you’d expect fans to be accustomed to it in football, which modifies its numerous rules constantly (in stark contrast to fútbol). Now, however, the game itself is threatened, and the worry is not simply that “football is football only if it is played on a 100-yard field by 22 children at a time,” but also that the game’s enemies are massing at the gate. Jon Gruden on the current state of affairs: “There are a lot of geniuses that are trying to damage the game, and ruin the game. Do you feel it? There are a lot of geniuses that want to eliminate all sports, including recess.”^

No Comments on "CTE part II: No, really, stop hitting yourself"