By: Patrick W. Zimmerman

From its inception, science fiction has exhibited a central tension, between optimists who saw technological change as a way to solve the majority of humanity’s problems (Star Trek and The Jetsons are two of the more happy happy joy joy examples) and pessimists who saw dystopian fields ahead (Orwell, Huxley, Zamyatin). Almost all works of sci-fi can be analyzed as social science fiction in that even the most whiz-bang planetary romance contains some social context. The progressivist idea that technological change is inevitable and, in most cases, linear, is perhaps the one ideology produced by the 19th century that achieved cultural hegemony during the 20th, both in the Capitalist World as well as the Socialist.

The standout lesson from this literary, cinematic, and (more recently) gaming legacy of dreaming, prognostication, calculation, future-telling, wonder, and scientific projection: we suck at predicting the future.

Seriously. With very few exceptions (Verne, Clarke), most of the great hopes (jetpacks!) and fears (Skynet!) to come out of science fiction have failed to come to pass.

The question

Then, why should we care about science fiction? Because, even if a story written in 1968 and set in 2001 has all the predictive power of Miss Cleo, it tells us an incredible amount about the culture, society, and politics of the time it was written.

Rather than nitpicking about the accuracy of some of the most influential pop culture of the last 100+ years (because it’s risible), let’s focus on what science fiction does tell us: how did the hopes, dreams, and fears expressed in science fiction evolve? What does that tell us about the times in which these works were made?

We should also care because these stories are awesome and gives a perfect opportunity to highlight some of the most interesting narratives of the last century-plus.

The short-short version

We’re getting gradually more pessimistic the longer we go without innovating our way to world peace, an end to poverty, higher bowling averages, and lower mini-golf scores.

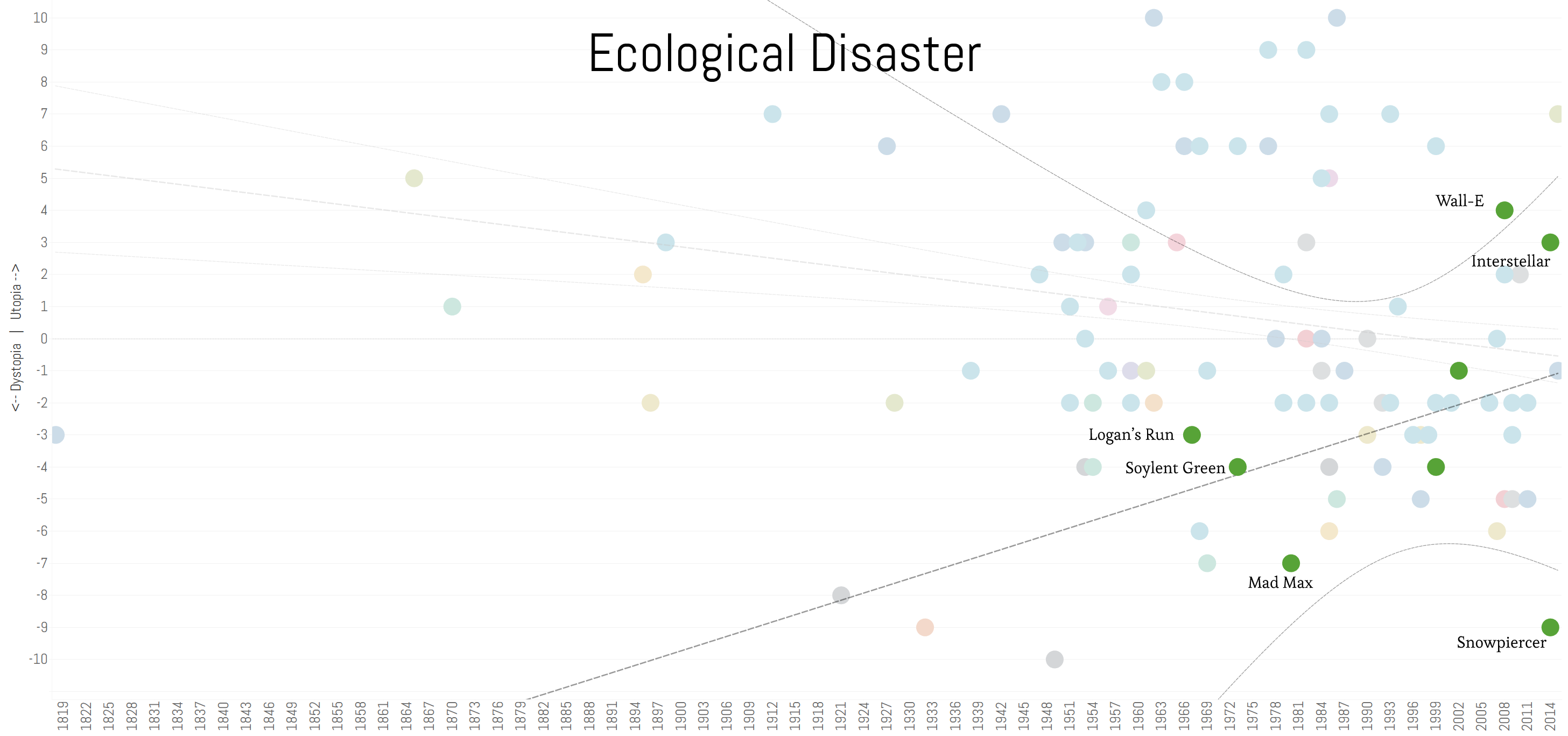

Except we’re weirdly optimistic about our chances of solving ecological disaster. Except for Snowpiercer.

The method

So, how do we measure this?

- Collect a sample of 100 of the more prominent works of science fiction, distributed between film, literature, TV, and games (plus one radio drama), and date the first airtime or publication of each narrative universe. I chose to not include superhero or comic books (Watchmen is a notable exception), primarily because those canons are totally bonkers with resets, contradictions, and other insanity. For some works, I made exceptions to the rule of primacy because a later publication was either significantly more well-known or different enough to qualify (most notably, Blade Runner as opposed to Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?).

- Assign each canon a series of subjects (artificial intelligence, cyberspace, alien contact, etc).

- Rate the work on a -10 to +10 scale, where -10 is utter soul-crushing dystopia and +10 is kumbaya pie-in-the-sky utopia. For this scale, I focused on two things:

- Is the narrative universe, taken holistically, predicting that technological change will have a largely positive or negative development on human society?

- Modified by “is there hope for us?”

- Drink another pan-galactic gargle blaster.

Note: The utopia rating is based on the super-scientific, patent-pending, ultra secret, proprietary Gut MethodTM. May not be reused without the express written consent of Major League Calvinball.

Note on the note: Submit petitions for changes in the utopia rankings in the comments below including 1) name of the work to change, 2) how much it should move, 3) detailed evidence as to why, and 4) who would win in a fight between a Martian tripod, an AT-AT, and a particularly angry Dalek.

Note II: the Creator field for visual works is usually given to the director for films, the show’s producer or writers for TV, and the studio for games. Exceptions are made when a single author is well-established.

Takeaways

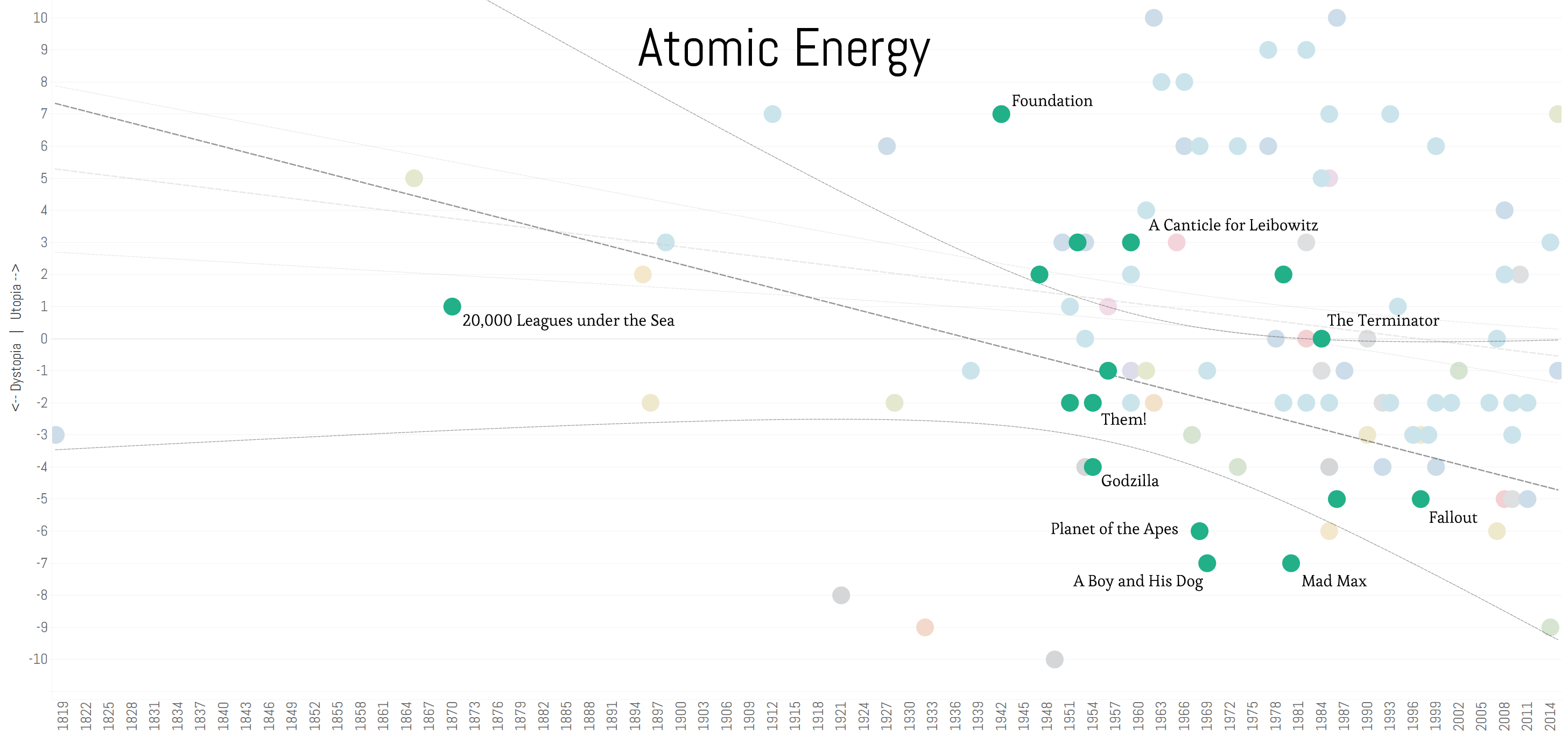

- Atomic energy was mostly a concern during the Cold War or with later works explicitly referencing the sci-fi tropes of the time (Fallout). It should surprise exactly zero people that authors were concerned about us blowing it all up during the latter half of the Twentieth Century, as the ” target=”_blank”>Doomsday Clock reached its most perilous setting in 1953 when we invented the hydrogen bomb. In the 1950s, whether you wanted to write about technology-as-magic or technology-will-kill-us-all, “Atomics” was your phlebotinum of choice. We were going to have atomic (flying) cars, atomic spaceships, atomic forcefields. It was going to be explosive fun.

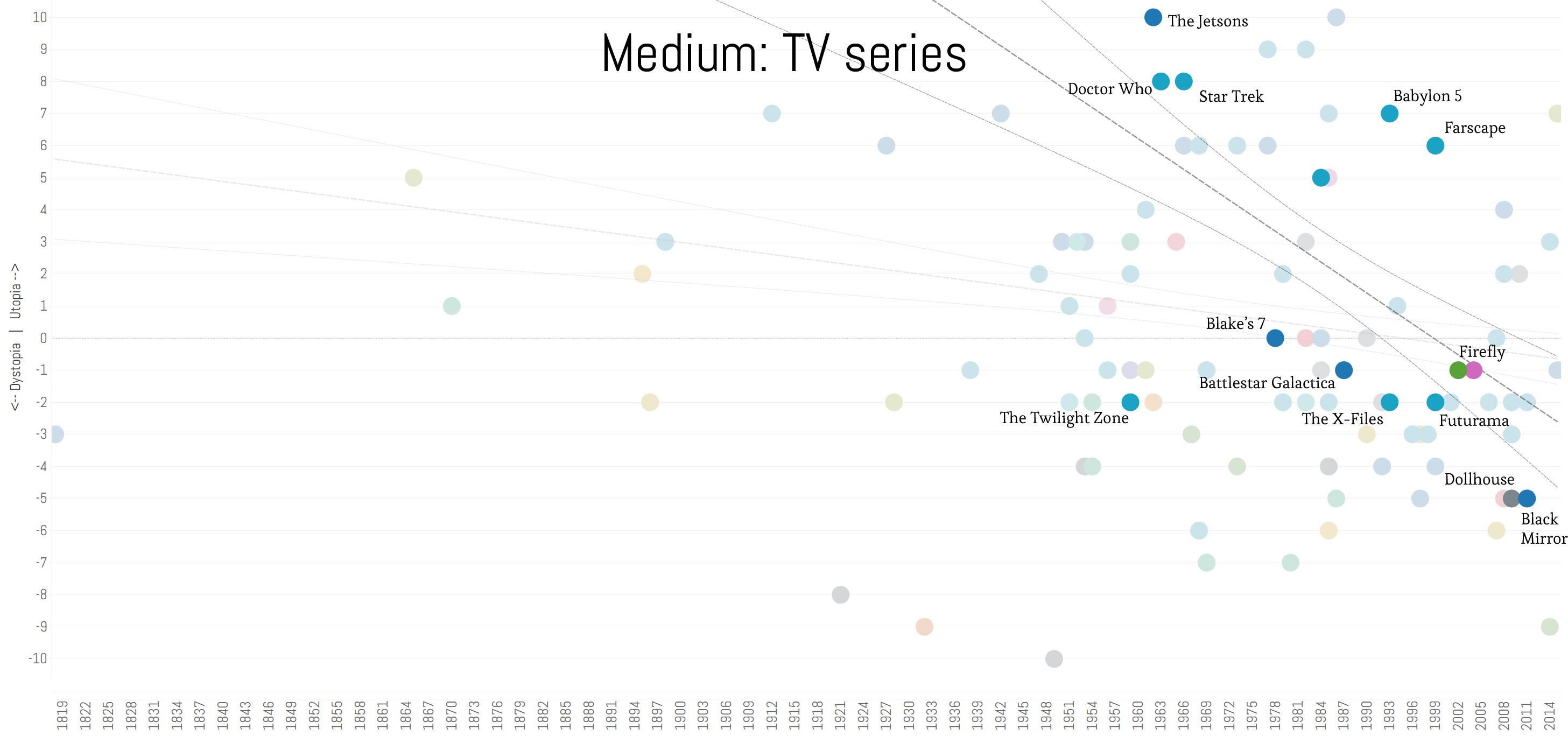

- Dystopia is IN on the small screen. Or, looking at it another way, The Twilight Zone was way, way ahead of its time as a cynical take on science fiction on TV. This is in contrast to the other major sci-fi media, as novels are holding pretty steady just around average and films are much more slowly shifting from utopic to dystopic. One possible explanation? The end of broadcast TV dominance. The vast expansion of cable channels in the 1990s and streaming services more recently has allowed TV to explore themes that would formerly have censured by the FCC or simply avoided by risk-averse Big Three network executives. Remember the environment before cable? Star Trek was told that it had to choose between the women and the Martian (Mr. Spock) because it was just too risqué to have both on the same show. Now contrast SyFy’s approach to The Expanse, which splatters the gore and boobs in a nearly Game of Thrones-esque fashion (the show is represented in the dB as the first book in the series, Leviathan Wakes).

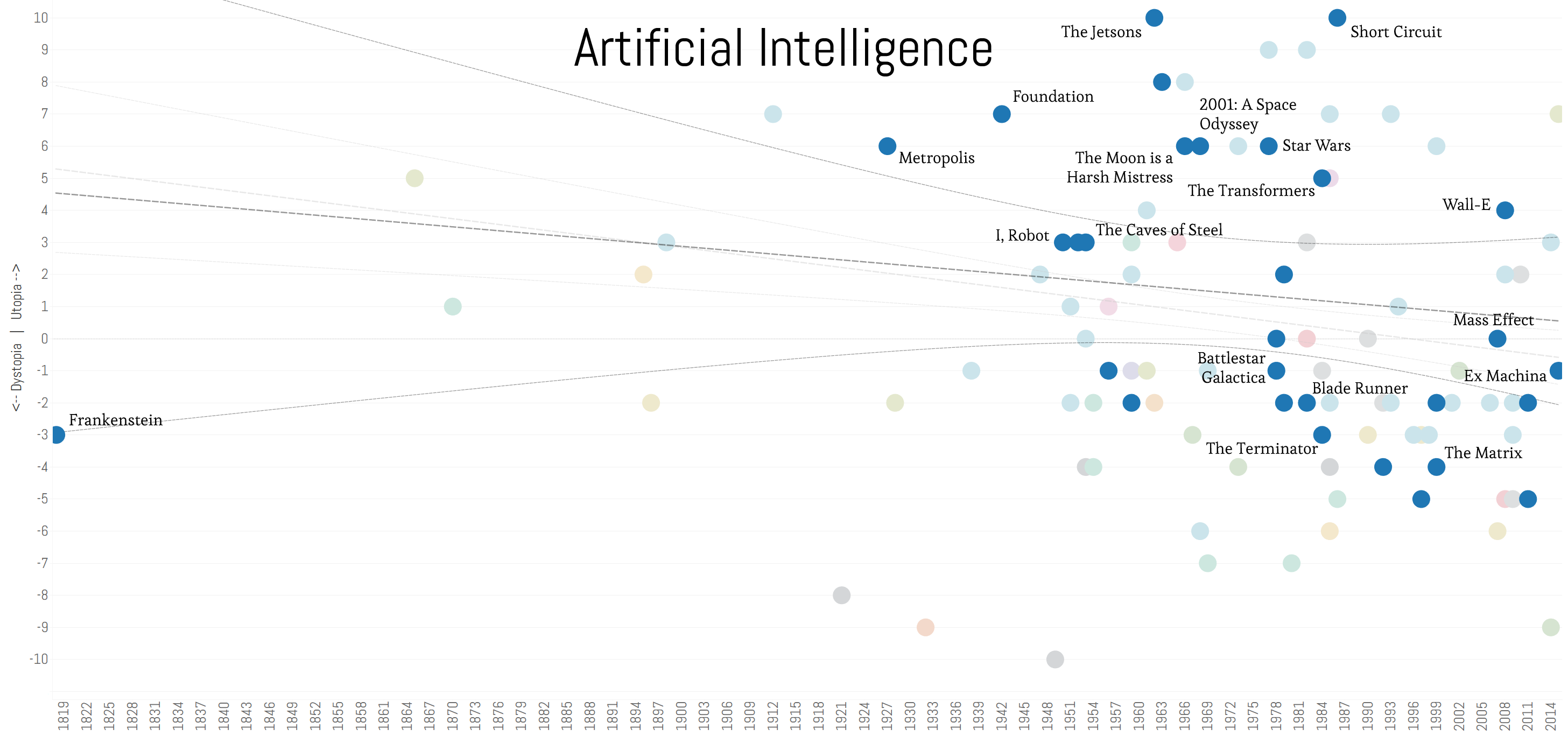

- We have no idea what to think about artificial intelligence. It’s the oldest science fiction theme there is (I am, not terribly controversially, dating things back to Frankenstein), and yet we’re still all over the frakking place with how we treat other organisms into which we breathe life. Short Circuit (+10) and The Terminator (-3) were created 2 years apart. But we keep trying, because it’s still one of the more popular subjects for science fiction.

- We’re weirdly optimistic about our chances to fix the environment. Considering that the effects of climate change are now part of the Doomsday Clock calculation, you’d think that we’d take this more seriously than we did in, say, the 1970s. Nope! In spite of the seemingly obvious dangers of toxic spills, the Greenhouse effect, and increased climate volatility to the stability of life in this single, self-contained ecosphere, it’s something that is still relatively rare as a subject in sci-fi, and in some cases (Wall-E, Interstellar, we can survive it). That seems….short-sighted (Except for Snowpiercer, which is about as dark as dark gets).

The full dashboard

Now, it’s your turn. Have at it, and see what interesting patterns you find!

You can search by subject, creator, or medium, and mouse-overs or clicks will pop up details on each datapoint.

Note: the dashboard only renders one subject at a time for each datapoint. So, while Star Trek will show up in a search for “space travel” and “time travel” and “artificial intelligence,” the tooltip will only display one of those at a time.

The final word

Most technological change is initially more inspiring than scary, at least in its pop-cultural depictions. We have more of a tendency to giddly imagine the endless possibilities of any new advance than we do to consider its potential for misuse. This more or less explains the gradual pessimistic slide of science fiction over time, as well as our broader habit of screaming, “For SCIENCE!!!!” at the first chance to resurrect dinosaurs using frog DNA. Our most prestigious scientific honor was born out of regret at this exact phenomenon.

The weird outliers? Apparently we’ve become more confident in our ability to deal with the potential dangers of ecological disasters and time travel. Yup, those are the only two subjects in the set with even the slightest upwards trendlines. Disregarding one-way time travel as a near-certainly-dead human popsicle, it shouldn’t be shocking that the Environment isn’t a bigger concern to authors. After all, we’re in an era of persistent, worldwide climate denial. And the second-largest emitter of CO2 in the world is led by a man who publicly espouses this:

The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 6, 2012

and this:

This very expensive GLOBAL WARMING bullshit has got to stop. Our planet is freezing, record low temps,and our GW scientists are stuck in ice

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 2, 2014

Yeah. You’re right. We’re boned.

No Comments on "The history of the future: Science fiction tells us a lot about our past (but stinks at predicting technological change)"